Martial Arts Weapons

NOTE: There are a wide variety of weapons in the world and the same cultural backgrounds that use them... In the System that I teach, "American Kempo Ninjuka Taijutsu", a lot of them are mainly from older katas from Okinawa, China and Japan, but were redone for Moo Duk Kwan Tang Soo Do, which is my base martial art when I started training...

Iaido

居合道

いあいどう

Iaido: Focus - Weaponry - Hardness

Forms competitions only.

Country of origin Japan

Parenthood

Iaijutsu Olympic sport - No

Iaido (居合道 Iaidō?), abbreviated with iai (居合?), is a modern Japanese martial art and sport that emphasizes being aware and capable of quickly drawing the sword and responding to a sudden attack.[

Iaido is associated with the smooth, controlled movements of drawing the sword from its scabbard (or saya), striking or cutting an opponent, removing blood from the blade, and then replacing the sword in the scabbard. While beginning practitioners of iaido may start learning with a wooden sword (bokken) depending on the teaching style of a particular instructor, most of the practitioners use the blunt edged sword, called iaitō. Few, more experienced, iaido practitioners use a sharp edged sword (shinken).

Practitioners of iaido are often referred to as iaidoka.

Origins of the name

Haruna Matsuo sensei (1925–2002) demonstrating Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu kata Ukenagashi

The term 'iaido' appear in 1932 and consists of the kanji characters 居 (i), 合 (ai), and 道 (dō). The origin of the first two characters, iai (居合?), is believed to come from saying Tsune ni ite, kyū ni awasu (常に居て、急に合わす?), that can be roughly translated as “being constantly (prepared), match/meet (the opposition) immediately”. Thus the primary emphasis in 'iai' is on the psychological state of being present (居). The secondary emphasis is on drawing the sword and responding to the sudden attack as quickly as possible (合).

The last character, 道, is generally translated into English as the way. The term 'iaido' approximately translates into English as "the way of mental presence and immediate reaction", and was popularized by Nakayama Hakudo.

The term emerged from the general trend to replace the suffix -jutsu (術?) ("the art of") with -dō (道?) in Japanese martial arts in order to emphasize the philosophical or spiritual aspects of the practice.

Purpose of iaido

Iaido encompasses hundreds of styles of swordsmanship, all of which subscribe to non-combative aims and purposes. Iaido is an intrinsic form of Japanese modern budo.

Iaido is a reflection of the morals of the classical warrior and to build a spiritually harmonious person possessed of high intellect, sensitivity, and resolute will. Iaido is for the most part performed solo as an issue of kata, executing changed strategies against single or various fanciful rivals. Every kata starts and finishes with the sword sheathed. Notwithstanding sword method, it obliges creative ability and fixation to keep up the inclination of a genuine battle and to keep the kata new. Iaidoka are regularly prescribed to practice kendo to safeguard that battling feel; it is normal for high positioning kendoka to hold high rank in iaido and the other way around.

To appropriately perform the kata, iaidoka likewise learn carriage and development, hold and swing. At times iaidoka will practice accomplice kata like kendo or kenjutsu kata. Dissimilar to kendo, iaido is never honed in a free-competing way.

Moral and religious influence on iaido

The metaphysical aspects in iaido have been influenced by several philosophical and religious directions. Iaido is a blend of the ethics of Confucianism, methods of Zen, the philosophical Taoism and aspects from bushido.

Seitei-gata techniques

Because iaido is practiced with a weapon, it is almost entirely practiced using solitary forms, or kata performed against one or more imaginary opponents. Multiple person kata exist within some schools of iaido; consequently, iaidoka usually use bokken for such kata practice. Iaido does include competition in form of kata but does not use sparring of any kind. Because of this non-fighting aspect, and iaido's emphasis on precise, controlled, fluid motion, it is sometimes referred to as "moving Zen." Most of the styles and schools do not practice tameshigiri, cutting techniques.

A part of iaido is nukitsuke. This is a quick draw of the sword, accomplished by simultaneously drawing the sword from the saya and also moving the saya back in saya-biki.

History

Early history (prior to the Meiji Restoration in 1868) read more in the article Iaijutsu.

Iaido started in the mid-1500s. Hayashizaki Jinsuke Shigenobu (1542 - 1621) is generally acknowledged as the organizer of Iaido. There were a lot of people Koryu (customary schools), however just a little extent remain today. Just about every one of them additionally concentrate on more seasoned school created amid 16-seventeenth century, in the same way as Muso-Shinden-ryu, Hoki-ryu, Muso-Jikiden-Eishin-ryu, Shinto-Munen-ryu, Tamiya-ryu, Yagyu-Shinkage-ryu, Mugai-ryu, Sekiguchi-ryu, et cetera.

After the collapse of the Japanese feudal system in 1868 the founders of the modern disciplines borrowed from the theory and the practice of classical disciplines as they had studied or practiced. The founding in 1895 of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (DNBK) 大日本武徳会 (lit. "Greater Japan Martial Virtue Society") in Kyoto, Japan. Was also an important contribution to the development of modern Japanese swordsmanship. In 1932 DNBK officially approved and recognized the Japanese discipline, iaido; this year was the first time the term iaido appeared in Japan. After this initiative the modern forms of swordsmanship is organised in several iaido organisations. During the post-war occupation of Japan, the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai and its affiliates were disbanded by the Allies of World War II in the period 1945–1950. However, in 1950, the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai was reestablished and the practice of the Japanese martial disciplines began again.

In 1952, the Kokusai Budoin, International Martial Arts Federation (国際武道院・国際武道連盟 Kokusai Budoin Kokusai Budo Renmei?) (IMAF) was founded in Tokyo, Japan. IMAF is a Japanese organization promoting international Budō, and has seven divisions representing the various Japanese martial arts, including iaido.

In 1952, the All Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR) was founded, and the All Japan Iaido Federation (ZNIR) was founded in 1948.

Upon formation of various organizations overseeing martial arts, a problem of commonality appeared. Since members of the organization were drawn from various backgrounds, and had experience practicing different schools of iaido, there arose a need for a common set of kata, that would be known by all members of organization, and that could be used for fair grading of practitioner's skill. Two of the largest Japanese organizations, All Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR) and All Japan Iaido Federation (ZNIR), each created their own representative set of kata for this purpose.

The role of Iaido in Kendo

Despite the fact that the purposes of assault in current Kendo are entirely restricted, the strikes and assaults are performed with an opportunity of will that definitely prompts a component of rivalry. In correlation with shinai Kendo, Iaido focus on preparing to create right developments. Therefore, regarding specialized immaculateness it involves a level much higher than that of shinai Kendo. In short, Iaido can serve to enhance and keep up specialized virtue in shinai Kendo. Iaido aides guarantee that body developments are legitimate and compelling in light of the fact that they are regular, precise, and spry.

Kata under the respective iaido organizations

Tōhō Iaido

The All Japan Iaido Federation (ZNIR, Zen Nihon Iaido Renmei, founded 1948) has a set of five koryu iaido forms, called Tōhō, contributed from the five major schools that comprise the organization.

*Musō Jikiden Eishin-ryū School founded during the late Muromachi period (ca. 1590). ('Mae-giri')

*Mugai-ryū School founded in 1695. ('Zengo-giri')

*Shindō Munen-ryū School founded in the early 1700s. ('Kiri-age')

*Suiō-ryū School founded during the early Edo period (ca. 1615). ('Shihô-giri')

*Hōki-ryū School founded during the late Muromachi period (ca. 1590). ('Kissaki-gaeshi')

Seitei Iaido

Seitei or Zen Nippon Kendo Renmei Iaido (制定) ("basis of the Iaido") are technical based on seitei-gata, or standard form of sword-drawing techniques, created by the Zen Nihon Kendo Remmei (All Japan Kendo Federation) and the Zen Nihon Iaido Remmei (All Japan Iaido Federation).This standard set of iaido kata was created in 1968 by a committee formed by the All Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF, Zen Nippon Kendo Renmei or ZNKR). The twelve Seitei iaido forms (seitei-gata) are standardised for the tuition, promotion and propagation of iaido at the iaido clubs, that are members of the regional Kendo federations. All dojos, that are members of the regional Kendo federations teach this set. Since member federations of International Kendo Federation (FIK) uses seitei gata as a standard for their iaido exams and shiai, seitei iaidohas become the most widely practised form of iaido in Japan and the rest of the world.

Other organizations

Single-style federations usually do not have a standardized "grading" set of kata, and use kata from their koryu curriculum for grading and demonstrations.

Iaido schools

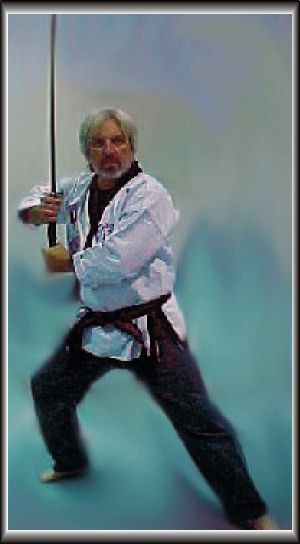

Iaido in the Czech Republic as demonstrated by Victor Cook Sensei

Many iaido organisations promote sword technique from the seiza (sitting position) and refer to their art as iaido. One of the popular versions of these is the Musō Shinden-ryū 夢想神伝流, a iaido system created by Nakayama Hakudō (1872–1958) in the 1932. The Musō Shinden-ryū is an interpretation of one of the Jinsuke-Eishin lines, called Shimomura-ha.

The other line of Jinsuke-Eishin, called Tanimura-ha, was created by Gotō Magobei Masasuke] (died 1898) and Ōe Masamichi Shikei (1852–1927). It was Ōe Masamichi Shikei who began formally referring to his iaido branch as the Musō Jikiden Eishin-ryū 無双直伝英信流 during the Taishō era (1912–1926).

Ranks in Iaido

Ranking in iaido depends on the school and/or the member federations to which a particular school belongs. Iaido as it is practiced by the International Kendo Federation (FIK) and All Japan Iaido Federation (ZNIR) uses the kyu-dan system, created in 1883.

Modern kendo is almost entirely governed by the FIK, including the ranking system. Iaido is commonly associated with either the FIK or the ZNIR, although there are many extant koryū which may potentially use the menkyo system of grading, or a different system entirely. Iaido as governed by the FIK establishes 10th dan as the maximum attainable rank, though there are no living 10th practitioners in Kendo, there still remains many in Iaido. While there are some living 9th dan practitioners of kendo, the All Japan Kendo Federation only currently awards up to 8th dan. Most other member federations of the FIK have followed suit, excluding Iaido.

International Iaido Sport Competition

Medals and cups are a part of iaido in connection with sport games.

Iaido, in its modern form, is practiced as a competitive sport, regulated by the All Japan Kendo Federation. The AJKF maintains the standardized iaido kata and etiquette, and organizes competitions.

An iaido competition consists of two iaidoka performing their kata next to each other and simultaneously. The competitors will be judged by a panel of judges according to the standardized regulations.

European Kendo Federation has arranged iaido championships since 2000...

Etymology and definition of Weapons

Okinawan

Okinawan kobudō is a Japanese term that can be translated as "old martial way of Okinawa". It is a generic term coined in the twentieth century.

Okinawan kobudō refers to the weapon systems of Okinawan martial arts. These systems can have from one to as many as a dozen weapons in their curriculum, among the rokushakubo (six foot staff, known as the "bō"), sai (dagger-shaped truncheon), tonfa (handled club), kama (sickle), and nunchaku (chained sticks), but also the tekko (steelknuckle), tinbe-rochin (shield and spear), and surujin (weighted chain). Less common Okinawan weapons include the tambo (short stick), the hanbō (middle length staff) and the eku (boat oar of traditional Okinawan design).

Okinawan kobudō should not be confused with the term Kobudō, which is described in the article Koryū, because the term Kobudō refers not to a weapon system but refers to a concept of moral from the feudal Japan.

History

It is a popular story and common belief that Okinawan farming tools evolved into weapons due to restrictions placed upon the peasants by the Satsuma samurai clan when the island was made a part of Japan, which forbade them from carrying arms. As a result, it is said, they were defenseless and developed a fighting system around their traditional farming implements. However, modern martial arts scholars have been unable to find historical backing for this story, and the evidence uncovered by various martial historians points to the Pechin Warrior caste in Okinawa as being those who practiced and studied various martial arts, rather than the Heimin, or commoner. It is true that Okinawans, under the rule of foreign powers, were prohibited from carrying weapons or practicing with them in public. But the weapons-based fighting that they secretly practiced (and the types of weapons they practiced with) had strong Chinese roots, and examples of similar weapons have been found in China, Malaysia and Indonesia pre-dating the Okinawan adaptations.

Okinawan kobudō systems were shaped by indigenous Okinawan techniques that arose within the Aji, or noble class and by imported methods from China and Southeast Asia. The majority of Okinawan kobudō traditions that survived the difficult times during and following World War II were preserved and handed down by Taira Shinken (Ryūkyū Kobudō Hozon Shinkokai), Chogi Kishaba (Ryūkyū Bujustsu Kenkyu Doyukai), and Kenwa Mabuni (Shito-ryū). Practical systems were developed by Toshihiro Oshiro and Motokatsu Inoue in conjunction with these masters. Other noted masters who have Okinawan kobudō katanamed after them include Chōtoku Kyan, Shigeru Nakamura, Kanga Sakukawa, and Shinko Matayoshi.

Okinawan kobudō arts are thought by some to be the forerunner of the bare hand martial art of karate,[citation needed] and several styles of that art include some degree of Okinawan kobudō training as part of their curriculum. Similarly, it is not uncommon to see an occasional kick or other empty-hand technique in an Okinawan kobudō kata. The techniques of the two arts are closely related in some styles, evidenced by the empty-hand and weapon variants of certain kata: for example, Kankū-dai and Kankū-sai, and Gojūshiho and Gojūshiho-no-sai, although these are examples of Okinawan kobudō kata which have been developed from karate kata and are not traditional Okinawan kobudō forms. Other more authentic Okinawan kobudō kata demonstrate elements of empty hand techniques as is shown in older forms such as Soeishi No Dai, a bo form which is one of the few authentic Okinawan kobudō kata to make use of a kick as the penultimate technique. Some Okinawan kobudō kata have undergone less "modern development" than karate and still retain much more of the original elements, reflections of which can be seen in even more modern karate kata. The connection between empty hand and weapon methods can be directly related in systems such as that formulated in order to preserve both arts such as Inoue/Taira's Ryūkyū Kobujutsu Hozon Shinko Kai and Motokatsu Inoue's Yuishinkai Karate Jutsu. M. Inoue draws direct comparisons between the use of certain weapons and various elements of empty hand technique such as sai mirroring haito/shuto waza, tonfa reflecting that of uraken and hijiate, and kama of kurite and kakete, as examples. The footwork in both methods is interchangeable.

Weapons and kata

Okinawans kobudō was at its zenith some 100 years ago and of all the authentic Okinawan kobudō kata practiced at this time, only relatively few by comparison remain extant. In the early 20th centuries a decline in the study of Ryūkyū kobujutsu (as it was known then) meant that the future of this martial tradition was in danger. During the Taisho period (1912–1926) some martial arts exponents such as Yabiku Moden made great inroads in securing the future of Ryūkyū kobujutsu. A large amount of those forms which are still known are due to the efforts of Taira Shinken who travelled around the Ryūkyū Islands in the early part of the 20th century and compiled 42 existing kata, covering eight types of Okinawan weapons. Whilst Taira Shinken may not have been able to collect all extant Okinawan kobudō kata, those he did manage to preserve are listed here. They do not include all those from the Matayoshi, Uhuchiku and Yamanni streams however.

Bō

The bō is a six-foot long staff, sometimes tapered at either end. It was perhaps developed from a farming tool called a tenbin: a stick placed across the shoulders with baskets or sacks hanging from either end. The bo was also possibly used as the handle to a rake or a shovel. The bo, along with shorter variations such as the jo and hanbo could also have been developed from walking sticks used by travelers, especially monks. The bo is considered the 'king' of the Okinawa weapons, as all others exploit its weaknesses in fighting it, whereas when it is fighting them it is using its strengths against them. The bo is the earliest of all Okinawan weapons (and effectively one of the earliest of all weapons in the form of a basic staff), and is traditionally made from red or white oak. Also most of the time they used dark oak for tournaments with the bō.

Sai

The sai is a three-pronged truncheon sometimes mistakenly believed to be a variation on a tool used to create furrows in the ground. This is highly unlikely as metal on Okinawa was in short supply at this time and a stick would have served this purpose more satisfactorily for a poor commoner, or Heimin. The sai appears similar to a short sword, but is not bladed and the end is traditionally blunt. The weapon is metal and of the truncheon class with its length dependent upon the forearm of the user. The two shorter prongs on either side of the main shaft are used for trapping (and sometimes breaking) other weapons such as a sword or bo. A form known as nunti sai, sometimes called manji sai (due to its appearance resembling the swastika kanji) has the two shorter prongs pointed in opposite directions, with another monouchi instead of a grip.

Tonfa

The tonfa may have originated as the handle of a millstone used for grinding grain. It is traditionally made from red oak, and can be gripped by the short perpendicular handle or by the longer main shaft. As with all Okinawan weapons, many of the forms are reflective of "empty hand" techniques. The tonfa is more readily recognized by its modern development in the form of the police Side-handle baton, but many traditional tonfa techniques differ from side-handle baton techniques. For example, tonfa are often used in pairs, while side-handle batons generally are not.

Nunchaku

A nunchaku is two sections of wood (or metal in modern incarnations) connected by a cord or chain. There is much controversy over its origins: some say it was originally a Chinese weapon, others say it evolved from a threshing flail, while one theory purports that it was developed from a horse's bit. Chinese nunchaku tend to be rounded, whereas Okinawan ones are octagonal, and they were originally linked by horse hair. There are many variations on the nunchaku, ranging from the three sectional staff (san-setsu-kon, mentioned later in this article), to smaller multi-section nunchaku. The nunchaku was popularized by Bruce Lee in a number of films, made in both Hollywood and Hong Kong. This weapon is illegal in New York State, Canada, and parts of Europe.

Kama

The kama is a traditional farming sickle, and considered one of the hardest to learn due to the inherent danger in practicing with such a weapon. The point at which the blade and handle join in the "weapon" model normally has a nook with which a bo can be trapped, although this joint proved to be a weak point in the design, and modern day examples tend to have a shorter handle with a blade that begins following the line of the handle and then bends, though to a lesser degree; this form of the kama is known as the natagama. The edge of a traditional rice sickle, such as one would purchase from a Japanese hardware store, continues to the handle without a notch, as this is not needed for its intended use.

Tekko

The tekko or tecchu is a form of knuckleduster, and primarily takes its main form of usage from that of empty-hand technique, whilst also introducing slashing movements. The tekko is usually made to the width of the hand with anything between one and three protruding points on the knuckle front with protruding points at the top and the bottom of the knuckle. They can be made of any hard material but are predominantly found in aluminium, iron, steel, or wood.

Traditional shields used in kobudō

The tinbe-rochin consists of a shield and spear. It is one of the least known Okinawan weapons. The tinbe (shield) can be made of various materials but is commonly found in vine or cane, metal, or archetypically, from a turtle shell (historically, the Ryūkyū Islands' primary source of food, fishing, provided a reliable supply of turtle shells). The shield size is generally about 45 cm long and 38 cm wide. The rochin (short spear) is cut with the length of the shaft being the same distance as the forearm to the elbow if it is being held in the hand. The spearhead then protrudes from the shaft and can be found in many differing designs varying from spears to short swords and machete-style implements.

Surujin

The surujin consists of a weighted chain or leather cord and can be found in two kinds: 'tan surujin' (short) and 'naga surujin' (long). The lengths are about 150–152 cm and 230–240 cm respectively. It is a weapon which can be easily hidden prior to use, and due to this fact can be devastatingly effective. In the modern era, found with a bladed instrument at one end and a weight at the other, the surujin techniques are very similar to those of the nunchaku. Leather cords are used for practice or kumite, whereas chains are favored for demonstration, but rope (most commonly of hemp) was the original material used.

Eku

The Okinawan style of oar is called an eku (this actually refers to the local wood most commonly used for oars), eiku, iyeku, or ieku. Noteworthy hallmarks are the slight point at the tip, curve to one side of the paddle and a roof-like ridge along the other. One of the basic moves for this weapon utilizes the fact that a fisherman fighting on the beach would be able to fling sand at an opponent. While not having the length, and therefore reach, of the bō, the rather sharp edges can inflict more penetrating damage when wielded properly.

Tambo

The tambo, sometimes spelled tanbo, is a short staff (compared to a bo, or a hambo) made of hardwood or bamboo. Its length is determined by measuring from the tip of the elbow to the wrist. Tambo can be used in pairs.

Kuwa

The hoe is common in all agrarian societies; in Okinawa, the kuwa has been also used as a weapon for as long as there have been farmers. Compared to garden-variety hoes, the handle tends to be thicker and usually shorter, both due to Okinawan stature, and the fact that much of the agriculture takes place on hillsides where long handles would be a hindrance. A classic shape of blade is a simple rectangle of steel with a sharp leading edge, but may also be forked with tines.

Hanbo

The hanbō is a middle length wood or bamboo stick, used for striking and joint locking techs. It measures about 90 cm, or can be made taking into account the length from the hip to the ankle.

Nunti Bo

The nunti bo is similar to a spear, but typically composed of a bo with a manji-shaped sai mounted on the end.

Sansetsukon

The sansetsukon is similar to a nunchaku, but has three sections of wood (or metal in modern incarnations) connected by a cord or chain.

You can do it, too! Sign up for free now at https://www.jimdo.com